A Worm who lived on Beach Street

According to a plaque on 109 Beach Street, the ‘war’s leading humorist lived there’. Writer Richard West unlocks the mystery.

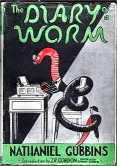

Many Deal locals as well as visitors to the Conservation area have been puzzled by a plaque on a Beach Street house in honour of ‘Nathaniel Gubbins, the war’s leading humorist who lived there from 1946 – 1957’.

Certainly as a twentieth century humorist, Gubbins lacked the celebrity status of Charles Hawtrey, the ‘Carry On’ actor whose plaque in Middle Street is a tourist attraction, although Hawtrey himself was not widely admired in Deal and was barred from most of its public houses.

Yet for those of us who remember the 1940’s, Gubbins’s articles in the Sunday Express captured the mood of an England exhausted by bombs, threats of invasion, rationing, queues and government propaganda. Certainly all our family looked forward keenly to Gubbins’s Sunday column as we did to his colleague J.B Morton; or ‘Beachcomber’ in the Daily Express.

Soon after the plaque appeared, I found that two of my friends in Deal, Nick and Audrey Roethenbaugh were not only fans of Gubbins but possessed the only existing anthology of his writing ‘The Best of Nathaniel Gubbins’, selected and introduced by Godfrey Smith, published by Blond & Biggs in 1978.

In his introduction, Smith laments that even twenty-five years ago, none of the wartime Gubbins’ collections were still available in a library, bookshop or even the publisher’s store room: ‘Poor Gubbins seemed to need the services of an archaeologist rather than of an anthologist. The hero of the Eighth Army and the darling of Lord Beaverbrook whose words were once savoured by millions, broadcast by the BBC and honoured by countless leaders in The Times is now well-nigh forgotten’.

In his opening column in 1933, Gubbins introduced himself to his readers as a ‘run-of-the-mill suburban chap’: ‘ I am 5ft 10 inches tall, weigh 13 stone and don’t look a day over ninety at six o’ clock in the morning. I hate regular meals, musical comedies, vivacious women, stewed steak and Christmas.

Although food figured large in Gubbins’s life, especially during the hungry years of war and rationing, he did not really mind vivacious women as long as they stuck to his favourite ‘low taverns’ and did not intrude on the home life ruled by his wife and her snobbish friends, especially the gas manager.

As early as 1936 and the Coronation of George V1, Gubbins liked to present himself as a ‘Worm’ under the harrow of domestic disapproval.

“Half–awake Worm hears his wife talking about Coronation. Hears mention of seats on route and mutters under bedclothes they’re seats only for very rich, much too expensive for clerk worms. Roused and fully awake Worm astonished to hear he is Bolshevik. Appears that Worm’s refusal to buy expensive Coronation seats has cast reflection on Worm’s loyalty. Patronising gas manager has already bought seats and lucky gas manager’s wife has new Coronation dress, but Worm’s wife who has misfortune to marry low socialist Worm who mixes with sweepings from the gutter will now be ashamed before whole of Worm’s Avenue.

Holidays are another cause of grievance to Worm’s long-suffering spouse. ‘Not content with keeping wife chained to Pigsty at Christmas, trying to make Christmas dinner out of skinny chicken and two ounces of bacon, while gas manager and his wife went to Switzerland; not content with taking wife for coach ride at Easter, while gas manager and wife went in limousine to Cornish Riviera, Worm is now going to take worn-out wife for week in cheap boarding house at Margate, while gas manager takes his wife for month to super hotel at Bournemouth with dwarf page boys in white jackets, lift to all floors and porter in scarlet and gold’.

Perhaps because he still hankered after those super hotels, Gubbins chose to retire across the road from the Royal in Deal. Like Mr and Mrs Pooter in The Diary of a Nobody, who always preferred to holiday in ‘Good old Broadstairs’, the Gubbins were horrified by Margate. ‘First morning in boarding house, Worm and wife arrive for breakfast. Arrival greeted by loud clapping led by ‘Bouncing Blond’ who is acknowledged boarding house wit and life and soul of party. ‘Worm seated next to Bouncing Blond who observes it is a great life if you don’t weaken. Appreciative Worm giggles. Bouncing Blond, encouraged, takes first bite of boarding house fishcakes and says, “well we’ve only got to die once”.

As a Great War veteran, Gubbins joined the Home Guard to fight off the threat of invasion in 1940. Whether or not he enjoyed himself, Home Guard Worm received little thanks for his military service.

‘After a morning of bayonet fighting in gas mask, attacking imaginary enemy over rough country, scaling walls and scrambling up steep sides of tank traps, Home Guard Worm returns exhausted with sore feet and pain in back. Home Guard Worm announces proudly that he has joined ‘Tough Squad’.

‘Oh, so sickly middle-aged Worm has joined Tough Squad has he? Wife might have known that show-off Worm, who is not even fit for fire-watching, would hardly be content with catching death of cold and spending half night prowling in dark after other Home Guard worms’.

Nathaniel Gubbins’ articles on the Home Guard were so well received by the services as well as civilians, that he was asked to report on life at sea, first on an oil tanker in a convoy leaving a Thames Estuary port and then on a Royal Navy mine layer, apparently in the English Channel.

Although the reports of sailor Gubbins are mostly concerned with the usual jokes about sea- sickness, cheap naval gin and whether to wear a life-jacket in bed, he does not let us forget that the voyages are in earnest. ‘Here on the tanker menaced by German torpedo vessels, it is midnight and we are in E-boat Alley’.

When he was not at sea or with his Home Guard platoon, Gubbins chronicled the everyday lives of the people of South-east London. After the threat of invasion in 1940, the subsequent Blitz and later rocket attacks, all of which were concentrated on Kent, Gubbins addresses the more mundane problems of getting about on public transport, keeping warm in winter and getting enough food to put on the table and giving an occasional treat to the cat.

If Nathaniel Gubbins was ‘the war’s leading humorist’ as is claimed by the plaque on his Beach Street house, his fame and Sunday Express column did not long survive the outbreak of peace. With his openly left-wing sympathies, Gubbins was not at ease on the paper owned by Lord Beaverbrook, a Tory cabinet minister and financial buccaneer.

But if Gubbins was acceptable during the war when the country was under a national government, his open delight at Labour’s victory in the 1945 general election must have got up the noses of the Sunday Express readers. It was time for the ‘Worm’ to retire to Deal and its wealth of ‘low taverns’.

©2006 “DEAL today” magazine